Introduction

The year was 331 BC. Two leaders of the ancient world; Alexander the Great and King Darius III, faced off in a showdown that altered the course of history. The Battle of Gaugamela was a test of strategy, courage, and sheer willpower. But how did Alexander, with fewer soldiers and seemingly insurmountable odds, emerge victorious? The answer might just surprise you.

Alexander the Great, son of Philip, and King of Macedon, launched the greatest campaign ever seen by the ancient world. He had set off from Macedon in 334BC with a force of about 40,000 troops. With this army he carried out an aggressive campaign, creating an empire that stretched from Greece to present day India. Before he got to India though, something stood in his way.

The Achaemenid empire, with Darius the Third at the helm of affairs.

The young Macedonian king defeated a large Persian force at Granicus, and sent Darius himself fleeing the battlefield the next year at Issus. He had also captured Darius’ wife, his mother, and his two daughters, Drypetis and Stateira II.

Darius tried to negotiate with Alexander three times. He offered to acknowledge him as co-monarch, but the Macedonian king declined. He offered money, lands and even the hand of one of his daughters in marriage. Alexander refused though, stating that there could only be one king in Asia, which would be decided in battle.

Lead up to The Battle of Gaugamela

Alexander crossed the Euphrates in the summer of 331 BC. Instead of taking a direct southeastern route to Babylon, he went north, keeping the Euphrates and the Armenian mountains on his left. He learnt that Darius had set up camp beyond the Tigris River which according to his intel, was undefended. This was because the Persians considered it impassable due to its strong current and depth.

Four days later, Alexander’s army spotted the Persian cavalry and captured a few members who revealed the location of Darius’ army at Gaugamela, a village situated along the Bumodus River, north of Arbela (present-day Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan), about eight miles away. Alexander concluded that Darius did not plan to relocate, allowing his troops four days of rest before the battle.

Macedonian Army

- Total Troops: Approximately 47,000 to 50,000 soldiers.

- Composition:

- Infantry: Around 32,000, including the elite Macedonian phalanx, Greek allied infantry, and mercenaries.

- Cavalry: Roughly 7,000, including the Companion Cavalry, Thessalian cavalry, and other allied horsemen.

- Other Units: Additional specialized troops, including archers and light infantry.

Persian Army

- Total Troops: Estimates vary widely, ranging from 100,000 to over 250,000 soldiers. Some ancient sources, like Arrian and Plutarch, exaggerated the number to as many as 600,000.

- Composition:

- Infantry: Likely over 100,000, including Persian infantry, various conscripts from across the empire, and Greek mercenaries.

- Cavalry: Estimates suggest around 30,000 to 40,000 cavalry, including the elite Persian horsemen and allied contingents.

- Scythed Chariots: Darius deployed around 200 scythed chariots, which were there to break the Macedonian phalanx.

- War Elephants: Darius also had 15 war elephants, which were a rare and intimidating sight on the battlefield.

The Battle

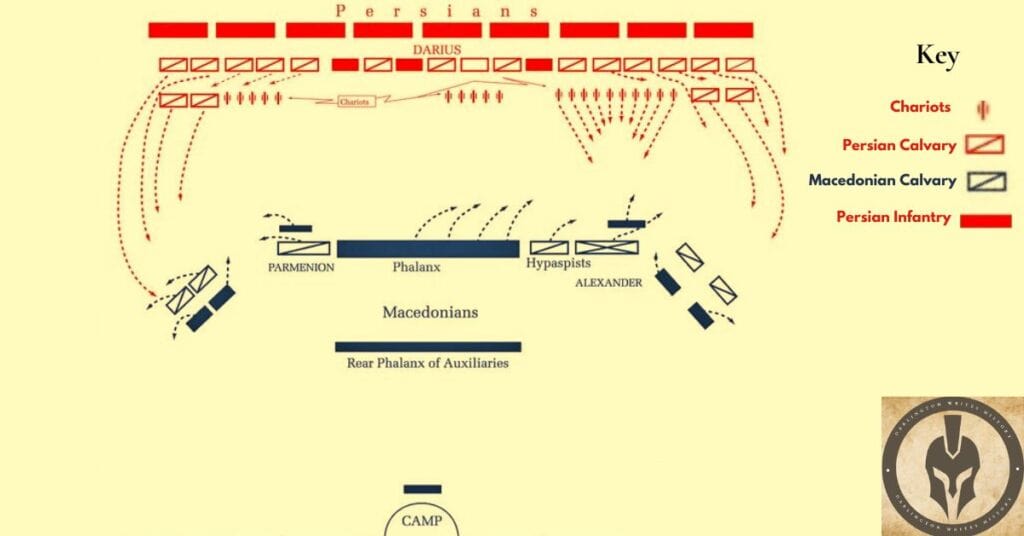

Troop Dispositions

Darius positioned himself at the center with his best infantry. On his right were Carian cavalry, Greek mercenaries, and Persian horse guards. In the right-center, he placed the famed Immortal Persian foot guards, and Mardian archers.

Cavalry units deployed on both flanks. Bessus commanded the Persian left flank, which included Bactrian, Dahae, Arachosian, Persian, Susian, Cadusian, and Scythian cavalry, with chariots placed at the front alongside a small group of Bactrians. Mazaeus commanded the right flank, consisting of Syrian, Median, Mesopotamian, Parthian, Sacian, Tapurian, Hyrcanian, Caucasian Albanian, Sacesinian, Cappadocian, and Armenian cavalry. The Cappadocians and Armenians led the attack, deployed ahead of the other cavalry units, while the Albanian cavalry went around to flank the Greek left.

The Macedonian forces had two sections, with Alexander commanding the right side and Parmenion the left. Alexander led his Companion cavalry, along with Paionian and Greek light cavalry. The mercenary cavalry had two groups: veterans on the right flank and the rest in front of the Agrians and Greek archers, positioned next to the phalanx. Parmenion deployed on the left with Thessalian, Greek mercenaries, and Thracian cavalry. He was tasked with holding the line while Alexander delivered the decisive blow from the right.

In the right-center were mercenaries from Crete, with Thessalian cavalry under Phillip and Achaean mercenaries behind them. To their right was another part of the allied Greek cavalry. The phalanx deployed in a double line. Despite being outnumbered over 5 to 1 in cavalry and having their line extended by over a mile, making it likely that the Greeks would be flanked by the Persians, the second line of mercenaries functioned to counter any flanking attempts.

Opening Moves

The battle of Gaugamela began with the infantry advancing in a phalanx formation toward the center of the enemy line. The Macedonians moved forward with their wings angled back at 45 degrees to entice the Persian cavalry into attacking. While the phalanxes engaged the Persian infantry, Darius ordered some of his cavalry and regular infantry to assault Parmenion’s forces on the left.

As the infantry engaged the Persian troops in the center, Alexander rode to the far edge of the right flank with his Companion Cavalry, moving away from the leveled ground. He wanted to draw as much of the Persian cavalry as possible to the flanks, creating a gap in the enemy line where he could deliver a decisive strike against Darius in the center. This strategy required precise timing, careful maneuvering, and Alexander’s leadership.

The Deciding Moment

Alexander kept on leading his troops in an echelon formation toward the right. Bessus responded by sending successive waves of Scythian and Bactrian cavalry. The mercenary cavalry engaged them, and despite being outnumbered, held their ground with support from the Paeonians. Before the phalanx could fully clear the leveled ground, Darius launched his chariots, but the javelineers and archers took down most of them before reaching the infantry, who then opened their ranks to allow the remaining chariots to pass through. After ordering his lancers to charge at the Scythians and Bactrians, Alexander continued his advance to the right. As more of the Persian left flank became engaged, a gap opened in their left-center.

Recognizing a critical moment, Alexander swiftly pivoted his forces to the left, leading the charge with his elite Companion cavalry, the hypaspists (his highly trained shield-bearers), and four formidable phalanx battalions. As they surged into the gap that had formed in the Persian lines, the impact was devastating. The combined force of the Macedonian cavalry and infantry, with their discipline and cohesion, overwhelmed the Persian center. The sudden and powerful assault caused panic and confusion among Darius’ troops, who were already stretched thin and struggling to maintain their positions.

Unable to withstand the relentless advance of Alexander’s forces, the Persian center began to crumble. Seeing his army faltering and fearing for his life, Darius was the first to abandon the battlefield, setting the stage for a complete rout. This marked a turning point in the battle of Gaugamela, as his troops lost both their leader and their will to fight.

The Pursuit

Recognizing the significance of Darius’ flight, Alexander sought to capitalize on the chaos. He quickly ordered his Companion Cavalry and other units to pursue the fleeing Persian king, aiming to capture or kill Darius and secure a decisive victory. However, due to the disarray on the battlefield and the sheer size of the Persian army, Alexander’s forces faced challenges in navigating through the fleeing soldiers.

While Alexander pursued Darius, the left wing of the Macedonian army, under Parmenion, was still engaged in a fierce battle against the remaining Persian forces. Parmenion, seeing the Persian forces crumbling after Darius’ departure, managed to hold his position and even began to push back the enemy. However, he soon sent a message to Alexander requesting assistance, as his forces were heavily outnumbered and struggling against the Persian cavalry on that flank.

Saving Parmenion

Fearing that Parmenion might be overwhelmed, Alexander made the strategic decision to break off the pursuit of Darius and return to support his general. Once he returned to assist Parmenion, the combined Macedonian forces successfully defeated the remaining Persian troops. With their army shattered and leaderless, the Persians were unable to mount any further resistance. The battle of Gaugamela ended in a decisive victory for Alexander, who had effectively crushed the last major Persian force.

The Aftermath

As the Macedonian forces secured the battlefield, they turned their attention to the Persian camp, which had been left largely undefended. The Macedonians looted the camp, seizing valuable treasures, supplies, and capturing many soldiers and camp followers who couldn’t flee. Among the spoils were Darius’ chariot, weapons, and personal belongings, symbolizing the complete victory of Alexander.

Darius escaped the battlefield by abandoning his royal chariot and fleeing on horseback with a small group of loyal followers. His escape was chaotic, forcing him to leave behind much of his royal entourage and possessions. Although he evaded capture, Darius was now a fugitive, with his authority as king severely diminished. Following the battle, Darius fled eastward in an attempt to gather new forces to continue the fight against Alexander. However, the defeat at Gaugamela made it nearly impossible for him to rally significant support. His former allies began to abandon him, and his satraps (provincial governors)lost faith in his ability to lead.

Despite this, Alexander did not immediately continue pursuing Darius after the battle of Gaugamela, as he focused on securing his newly acquired territories and consolidating his power. Over the following months, however, Alexander’s pursuit of Darius continued relentlessly. This led to Darius’ betrayal and assassination by Bessus, marking the end of his reign and the solidification of Alexander’s dominance over the Persian Empire.

Conclusion

The Battle of Gaugamela was devastating for the Persian forces. Estimates suggest that Darius III’s army suffered significant casualties, with tens of thousands of Persian soldiers killed or wounded. The exact number of casualties is difficult to pinpoint, but the defeat was catastrophic for the Persian military.

In contrast, the Macedonians suffered minimal losses compared to the scale of the Persian defeat. The Macedonian forces experienced few hundred casualties, reflecting Alexander’s effective strategy and the chaotic collapse of the Persian army.