Introduction

Humans have been fighting wars for many different reasons, both morally justifiable and absurd. But can you believe that one of the pettiest conflicts in history was over something as mundane as a bucket? In today’s post I bring to you, The War of The Bucket.

The War of the Bucket was a bizarre yet true tale from 1325 between the Italian city-states of Bologna and Modena. I know that this conflict sounds more like a comedic skit than a historical event, but it actually resulted from long-standing rivalry and tension.

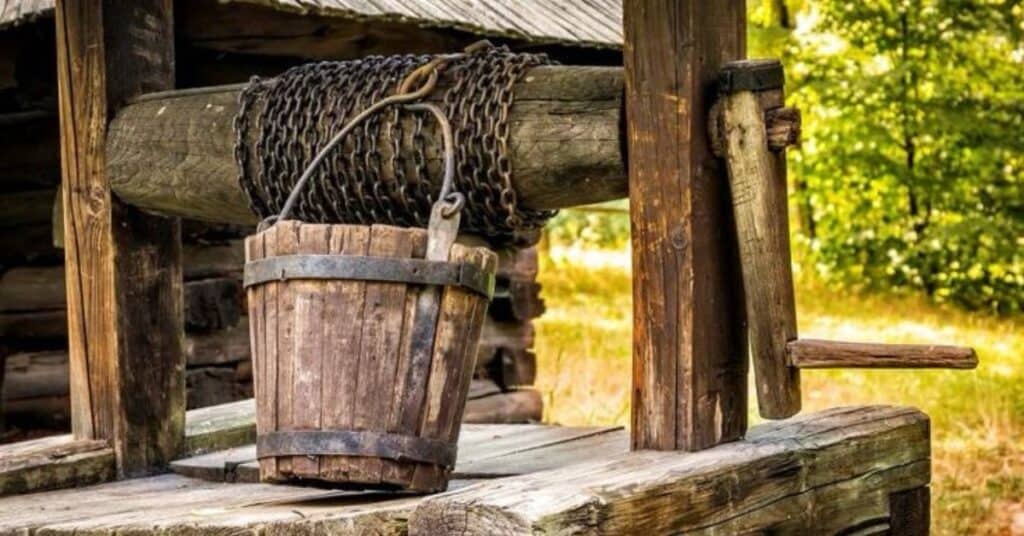

The story goes that in 1325, soldiers from Modena managed to steal a bucket from Bologna’s town well. This act of petty theft was the result of a full-blown battle where Modena, with numerically inferior but tactically superior forces, defeated Bologna, capturing not just the bucket but also many prisoners.

This war was short, with only about two days of actual fighting, but its absurdity makes it a very interesting historical event. The bucket itself is now displayed in Modena’s Ghirlandina Tower, serving as a peculiar trophy of this comical chapter in Italian history.

Let’s get started

Background

Medieval Italy wasn’t a unified kingdom, but rather a region of constantly warring principalities, ruled by wealthy noble families.

In medieval Italy, numerous principalities, republics, and territories existed, including the Kingdom of Naples, the Papal States under the Pope, the Duchy of Milan under the Visconti, the maritime Republic of Venice, the Republic of Florence, the Republic of Genoa, the Duchy of Ferrara ruled by the Este, Mantua under the Gonzaga, the Marquisate of Saluzzo, Siena as a republic, Lucca, Pisa, Urbino, Perugia, Bologna with papal influence, Modena tied to the Este family, Parma, Verona initially under the della Scala, Padua, Rimini governed by the Malatesta, Forlì by the Ordelaffi, and Faenza by the Manfredi.

This was a period that came after the collapse of the Roman empire, and a bunch of kingdoms popped up all over the continent. These rulers often fought and jostled to be able to decide who became the Pope, because having the Pope in your pocket was essentially having the church in your pocket.

Now, I know that this sounds like heresy, but some of the Popes at that point didn’t appear to be very upstanding followers of Christ.

Why?

Problems with the Papacy

Europe was a political boiling pot, and the kings of Europe fought to put their people in important places in the church. As a result, a lot of bishops or cardinals in the church got their positions because they were relatives or children of noblemen.This is called nepotism, and because of this, nobody really asked if you were good enough for the role.

Take for instance Pope John XII, who became a Pope because he was a son of one of the Counts of Tusculum, a wealthy Roman family that dominated Italian politics for centuries. They were secular noblemen, and this meant that they were more or less neutral in regards to religion of any sort.

FYI, by secular I don’t mean anti-religious. Just neutral.

The Badboy Pope

Now, Pope John XII became the Pope between the ages of 17-24 years old. Being a secular nobleman, he didn’t know much about the liturgy and all that. He wasn’t exactly an upstanding christian either, so he held lavish nude parties wherever he wanted in the Lateran Palace. He was alleged to celebrate mass without taking communion–an unheard of taboo for the Supreme Pontiff, ordaining a deacon in a horse stable, and receiving money from a noble to ordain his ten year old son as a bishop in the city of Todi.

There were also allegations about his adultery. They said he fornicated with the widow of Rainier, Stephana his father’s concubine, the widow Anna, and his own niece. It was almost like the sacred palace was his personal whorehouse.

More allegations popped up of him killing his own confessor, the cardinal subdeacon John (after castrating him), hunting publicly, toasting to the devil with wine, invoking Jupiter, Venus and other demons while playing dice, and not making the sign of the cross. There were more, but I’m sure you get the point.

He was more pimp than Pope.

John XII was said to have met his end at the hands of an enraged husband who caught him doing the thing that Popes aren’t supposed to be doing. With his wife. The husband–once more, allegedly –picked Johnny XII up and tossed him out a tower window, where he fell on the stone floor and died.

What a HARD way to die. Pun intended.

The Investiture Controversy

The story here is that the rulers of Europe liked to make their own relatives Pope so that they could easily control him and increase their power. Around the 800s AD this was the case with the Frankish King Charlemagne, who wanted more power, but lacked the legitimacy to back it up. This was solved when he had Leo III made the Pope in exchange for Frankish protection. So when the Frankish Empire was created, Charlemagne was its first emperor.

Charlemagne soon found out that being crowned by the Pope meant that he could be deposed by the Pope. The Pope too felt he was less powerful than the Emperor since the same Emperor made him the Pope.

Nobody really knew who was the boss at that point.

You’re wondering how this caused The War of the Bucket, but stay with me.

Much later, the Pope and the Emperor stopped being friends, since one felt threatened by the other. The Frankish Empire later disintegrated into France and The Holy Roman Empire, a federation of very disparate regions and principalities that spanned from Southern Denmark to Northern Italy. Many of these principalities spent their time rebelling against the Emperor. Some of these principalities were ruled by bishops and abbots, and technically the Emperor had no right to remove them. That was the Pope’s job.

Reports soon reached the Pope that the Holy Roman Emperor was selling church positions to his friends to place them in seats of power and boost his own authority.

This caused serious strife between the Pope and the Emperor.

Northern Italy, was separated from the rest of the Holy Roman Empire by the Italian Alps. This area, formerly called Cisalpine Gaul by the Romans, got the name Lombardy at this time. This region fell under heavy Papal influence, to the detriment of the Emperor.

A new Pope popped up, and he wanted to stop the abuse of the church being perpetrated by the Emperor.

Pope vs Emperor

Unfortunately for the Holy Roman Empire, and very fortunately for the church, The Emperor contracted tuberculosis and died, leaving his six year old son to take charge. The church wasted no time in using the naivety of the child Emperor to reset some rules. The Pope got the Emperor to agree to sign a rule stating that only a church-appointed group of cardinals could elect the Pope.

The Pope also used this period to get a bunch of twisted powers into his closet, including the right to depose emperors. By now Emperor Henry IV was a man, and he realised he had been played. He marched to the Pope and deposed him.

The Pope in retaliation, deposed the Emperor.

The Emperor, because he was the Emperor, deposed the Pope again.

The Pope, because he was the Pope, redeposed the Emperor too.

Eventually the issue was settled and Henry was forced to apologise to the Pope. This issue, called The Investiture Controversy, would pop up for many more years to come.

The War of The Bucket

Guelph vs Ghibelline

As at the twelfth century, there was a divide in Northern Italy between territories who supported the Pope and those that supported the Emperor. These two factions had a lot of infighting going on amongst them. The Emperor came down to assert his dominance in Northern Italy, and a group of cities formed The Lombard League and united to counter the external threat. With the Pope’s support they defeated the Emperor and sent him back to Germany.

When the Emperor left, these cities started fighting each other again.

In Italy, families and cities had two major factions. There were the Guelph, who supported the Pope and the Ghibelline, who supported the Emperor.

There were also the neutrals, but as we all know, neutrality doesn’t necessarily equal peace. These neutral people mostly fought each other and the other factions.

Now with the background done, we can get on to the actual war.

Modena vs Bologna

Modena was a Ghibelline state, while Bologna was Guelph. They went to war in 1249, and Bologna won, catapulting a live donkey into Modena afterwards. I don’t understand how that was supposed to be an insult, maybe some practical pun in 13th century Italian, but it worked. The Modenese were incensed, and tensions worsened, with both cities organising small raids and incursions into each other’s territory.

In 1325, Modenese soldiers sallied out and took Forte Monteveglio, one of the two forts protecting Bologna in the south. It was during this time that Modenese soldiers were accused of sneaking into Bologna one night and stealing a bucket from the well in the city.

This story though, has been labelled as false by modern historians. They argue that the war didn’t likely happen solely because of the bucket and even if the bucket was stolen, it happened at the end of the battle when the Modenese took it as a trophy of some sorts. The major cause of the war was differences and enmity between Guelph Bologna and Ghibelline Modena.

Now you might be thinking, “why was it called The War of the Bucket then?”

It was because there was actually a bucket involved.

The Battle of Zappolino

Bologna, incensed by the loss of their fort to Modena, mustered an army of thirty two thousand men. The Modenese had about seven thousand more experienced and better equipped troops.

Bologna sent a portion of the army to lay siege to the fort and the rest to prevent the Modenese from crossing the river. The men from Modena, more experienced, fewer in number and therefore highly mobile, crafted a clever ruse of pretending to attack further north. When the Bolognese rushed everybody up to attack them, they swung south and outmanoeuvred their enemies to go for the second fort at Zappolino. Bolognese men rushed to Zappolino where they finally clashed.

Bologna was routed, and they ran back to their city. The Modenese followed them all the way to their city gate, and this was where they STOLE THE BUCKET.

They moved it to their city hall, and it’s still there on display today.

Conclusion

Bologna lost about 2500 men, and Modena lost 500. Bologna and Modena held peace talks and Bologna agreed to pay for war damage. Modena kept the bucket, as a trophy for winning a war without much consequence in Italian politics. Thing is, there’s nothing like the attachment humans have for symbolic things. It pushes us to do what we wouldn’t rationally do, and in that haze of sentimental emotion, we descend into our most primal state. Even if it is for an old, creepy, oak bucket.

And so the War of the Bucket ended, with Modena hoisting the bucket high as a symbol of their victory in a story that perfectly showcases the absurdity and pettiness that can drive human conflict.